The Paper of the Month March

28 Feb 2022Infertility, Miscarriage, Stillbirth, and the Risk of Stroke Among Women: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Title: Which factors contribute to increased stroke risk in women during their reproductive years?

Author: Prof. Anita Arsovska, Associate Commissioning Editor, WSA

This article is a commentary on the following

Summary:

The authors have analyzed the association between infertility, miscarriage, and stillbirth, with stroke incidence (1). They have carried out a comprehensive literature search, comprising 7 808 521 women from 16 cohort and 2 case-control studies. The authors showed that women who had experienced miscarriage or stillbirth were at higher risk of stroke (miscarriage: HR, 1.07 [95% CI, 1.00–1.14]; stillbirth: HR, 1.38 [95% CI, 1.11–1.71]) than other women at reproductive age. The HRs of stroke for each additional miscarriage and stillbirth were 1.13 (95% CI, 0.96–1.33) and 1.25 (95% CI, 1.06–1.49), respectively. In subgroup analysis, increased risk of stroke was associated with repeated miscarriages and stillbirths (miscarriage ≥3: HR, 1.42 [95% CI, 1.05–1.90]; stillbirth ≥2: HR, 1.14 [95% CI, 1.04–1.26]). The authors argue that possible mechanisms leading to stroke could be common causes of pregnancy loss, such as endothelial dysfunction, elevated level of homocysteine, alloimmune and autoimmune factors, including the presence of antiphospholipid antibodies. Regarding genetic mechanisms, a novel synonymous FII c.1824C>T (variant located in the last exon of the prothrombin gene), has been reported, as a potential risk factor for pregnancy loss and was associated with prothrombotic state, cerebrovascular insult, and acute stroke.The authors have concluded that miscarriage and stillbirth are associated with an increased risk of stroke among women, which could be a proxy measure or a contributing risk factor to help identify women at higher risk of stroke.

Commentary:

Each year 55 000 more women than men have a stroke. The stroke incidence in women is 59 per 100000, which is slightly lower than men (62.8), but the mortality is higher (39.2% compared to 26.3% in men).Young women (less than 59 years) have a similar prevalence of stroke as men; in the higher age groups (more than 80 years), there is a female dominance, mainly due to the higher life expectancy of women. (2).

Beside nonmodifiable risk factors for stroke (such as age, genetics and race), there are several modifiable risk factors. Some of them are exclusive to women throughout the lifetime and occur at different ages (hormonal disturbances that affect age at menarche and menopause, use of hormone therapy, such as oral contraceptives, gender-affirming hormone therapy and hormone replacement therapy) as well as periods of pregnancy and postpartum (3,4).

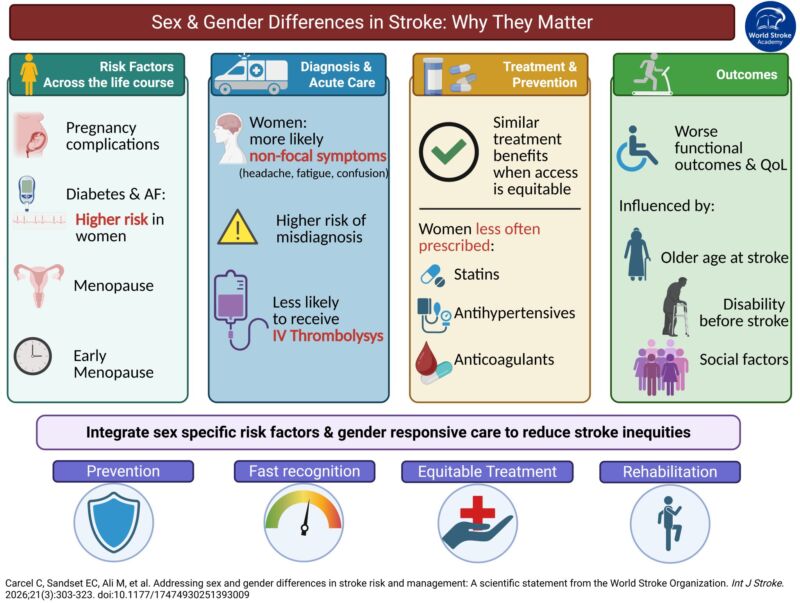

There are differences in conventional stroke risk factors (Figure 1). A recently published study outlined current knowledge of impact of sex and gender on stroke, showing that there are substantial differences in the strength of association of stroke risk factors, as well as female-specific risk factors (5).

Figure 1. Sex differences in stroke risk factors; size of figures indicates differences in strength of association between the given risk factors and stroke. GAHT- gender-affirming hormone therapy, MHT- menopausal hormone therapy

Adapted from Rexrode et al. 2022; Design by Florencia Casagrande, WSA Communication specialist

Compared to men, hypertension is lower in women in younger age groups, and it is higher in older age groups. In younger age groups, women are more likely to have blood pressure controlled; in older age groups, women are less likely to have blood pressure controlled. Dyslipidemia is lower in women, but women are less likely to be on statins and have LDL controlled. Atrial fibrillation is higher in women, but women are less likely to be prescribed oral anticoagulants, less likely to have cardiac ablation, and they receive lower doses of NOACs (,6,7).

During pregnancy, there is a significant increase in hormonal activity with significant cardiovascular, hemodynamic and coagulation changes. All these physiological gestational adjustments can predispose pregnant women to the occurrence of cerebrovascular disorders.The reported incidence of stroke varies from 25–34 cases per 100,000 deliveries. The rate of stroke is increased by ninefold at the time of delivery and threefold in the early postpartum period, with an increase in the risk of both ischaemic and haemorrhagic stroke (8, 9).Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy (HDP), a spectrum that includes gestational hypertension (blood pressure>140/90 mmHg), pre-eclampsia (hypertension with proteinuria) and eclampsia (seizures) are a leading cause of maternal and perinatal morbidity and mortality worldwide. Eclampsia and preeclampsia are the strongest risk factors for both ischemic stroke and intracerebral hemorrhage accounting for 24% to 48% of all pregnancy-associated strokes; this risk is potentiated by preexisting genitourinary tract infection, chronic hypertension, prothrombotic states, and coagulopathies ( 10, 11, 12).There is evidence that women with pregnancy outcomes of preterm birth and small for gestational age infants have higher rates of cerebrovascular events even after adjusting for other pregnancy complications. For women with prior stroke, the risk of recurrent stroke is increased in the peripartum and postpartum periods. The absolute risk of recurrent stroke associated with pregnancy is 0.7%, similar to the <1% yearly risk of recurrent stroke among young adults who have no vascular risk factors. The absolute risk depends on the presence of vascular risk factors or a definite cause of stroke, including thrombophilic disorders (13).The presence of a patent foramen ovale in pregnancy is associated with an increased risk of stroke in individuals with prothrombotic risk factors, including activated protein C resistance and reduced blood levels of protein S. However, in contrast to the risk of stroke from other factors, the risk owing to a patent foramen ovale peaks during the first and second trimesters of pregnancy (14). Pregnant women with hypercoagulable states should be considered for antithrombotic therapy with low-molecular-weight heparin. A careful evaluation, using a validated numerical risk assessment model, of all known preexisting, pregnancy-related and transient risk factors in both antepartum and postpartum periods is crucial to identify moderate−/high-risk women who could benefit from antithrombotic prophylaxis (15).

Another risk factor is use of hormonal contraceptives. Hormonal contraceptives, including oral, transdermal, and vaginal formulations, are effective and are used worldwide by >100 million women.There are various formulations containing either combined estrogen and progestogen or progestogen alone, administered as pills, patches, and rings (16). Combined oral contraceptives, comprising of estrogen and progestogen, are thrombogenic and have been associated with increased cardiovascular risk (17). The incidence of stroke associated with hormonal contraceptives is very low(21.4 per 100,000 person–years) (16). Low-dose oestrogen has been associated with a reduced stroke risk, and progestogen-only hormonal contraceptives havenot been associated with increased risk ofischemic stroke(18).

The risk of stroke in patients with Women with migraine who also use combined contraceptives have a further increased risk of ischemic stroke, where women with migraine with aura, use of contraceptives and who are active smokers have a dramatically elevated risk for stroke (20).

Conclusion:

It is important to be aware of stroke risk factors specific to women and to create individualized stroke prevention strategies. We need AI-based tools to proper identify specific factors associated with an increased incident risk of stroke among women. The future approach is probably precision medicine in stroke that will identify and analyse multiple variables obtained from each individual to create optimal stroke management.

References:

- Liang C, Chung HF, Dobson AJ, Mishra GD. Infertility, Miscarriage, Stillbirth, and the Risk of Stroke Among Women: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Stroke. 2022 Feb;53(2):328-337. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.121.036271.

- Virani SS, Alonso A, Benjamin EJ, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics-2020 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2020; 141(9): e139–e596

- Demel SL, Kittner S, Ley SH, McDermott M, Rexrode KM. Stroke Risk Factors Unique to Women. Stroke. 2018 Mar;49(3):518-523. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.117.018415.

- Corbière S, Tettenborn B. Stroke in women: Is it different? Clinical and Translational Neuroscience. January 2021.doi:1177/2514183X211014514.

- Kathryn M. Rexrode KR, Madsen TE, Amy YX et al. The Impact of Sex and Gender on Stroke. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.121.319915

- Madsen TE, Howard VJ, Jiménez M et al.Impact of conventional stroke risk factors on stroke in women an update. Stroke. 2018;49(3):536-542.

- Carcel C, Woodward M, Wang X et al. Sex matters in stroke: A review of recent evidence on the differences between women and men. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2020 Oct;59:100870. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2020.100870.

- Grear KE, Bushnell CD. Stroke and pregnancy: clinical presentation, evaluation, treatment and epidemiology. Clin. Obstetr. Gynecol.2013; 56, 350–359.

- Feske SK, Singhal AB. Cerebrovascular disorders complicating pregnancy. In: Continuum, Ed. American Academy of Neurology 2014. Continuum (Minneap Minn). 2014;20:80–99.

- Bushnell, C, Chireau M. Preeclampsia and stroke: risks during and after pregnancy. Stroke Res. Treat. 2011; 858134 .

- Kittner SJ, Stern BJ, Feeser BR, et al. Pregnancy and the risk of stroke. N Engl J Med. 1996;335(11):768-774. doi:10.1056/NEJM199609123351102

- Salonen HR, Lichtenstein P, Bellocco R et al. Increased risks of circulatory diseases in late pregnancy and puerperium. Epidemiology.2001; Vol 12, 456-460.

- Bushnell C, McCullough LD, Awad IA et al. Guidelines for the prevention of stroke in women: a statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke, 45, 1545-1588.

- Chen L, Deng W, Palacios I, et al. Patent foramen ovale (PFO), stroke and pregnancy. J Investig Med. 2016;64(5):992-1000. doi:10.1136/jim-2016-000103

- Papadakis E, Pouliakis A, Aktypi Α et al.Low molecular weight heparins use in pregnancy: a practice survey from Greece and a review of the literature. Thrombosis J 17, 23 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12959-019-0213-916.

- Daniels K, Mosher W, Jones J. National health statistics reports: contraceptives methods women have ever used: United States, 1982–2010 (CDC, 2013)

- Cordonnier C, Sprigg N, Sandset EC, et al. Stroke in women – from evidence to inequalities. Nature reviews. Neurology. 2017 Sep;13(9):521-532.

- Roach RE, Helmerhorst FM, Lijfering WM. et al. Combined oral contraceptives: the risk of myocardial infarction and ischemic stroke. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;27(8):CD011054.

- Schürks M, Rist PM, Bigal ME et al. Migraine and cardiovascular disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2009;339:b3914.

- Xu Z L Y, Tang S, Huang, X, Chen T. Current use of oral contraceptives and the risk of first-ever ischemic stroke: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Thromb. Res. 2015; 136, 52–60 .

Author interview:

Professor Gita Mishra, FAHMS PhD CStat

1. What did you set out to study?

To study the relationship of infertility, miscarriages, and stillbirths with subsequent stroke events.

2. Why this topic?

Stroke is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality around the World. More women than men suffer stroke, and they experience worse outcomes after stroke. We wanted to understand the drivers of this sex-difference and whether female-specific reproductive factors may contribute to this difference.

3. What were the key findings?

We found that women who had recurrent miscarriage and stillbirth were at an increased risk of stroke, however the evidence for infertility was inconclusive.

4. Why is it important? Or how might these results impact clinical practice?

From the study design, we were not able to say that recurrent miscarriage and stillbirth caused stroke, but these reproductive factors can be used as a marker for her future health risk. Clinicians may consider information on a woman’s history of repeated pregnancy loss or stillbirth as part of their assessment for stroke risk and in decisions on advice and treatments to reduce risk.

5. What surprised you most?

The relationship was evident even as a dose response between the number of miscarriages and stillbirths and the increased risk of stroke events.

6. What’s next for this research?

We will delve deeper into the relationship using individual-level data from a large international consortium to unpick the associations between recurrent miscarriage, stillbirth, and stoke subtypes.

7. Is there anything you’d like to add?

This study has highlighted the potential role of female-specific factors in the development of CVD.