The Paper of The Month – July

29 Jul 2023Title: Optimal timing of anticoagulation with direct oral anticoagulants in patients with ischemic stroke and atrial fibrillation

Title: Optimal timing of anticoagulation with direct oral anticoagulants in patients with ischemic stroke and atrial fibrillation

Author: Prof. Dr. Anita Arsovska – WSA Associate Commissioning Editor

This article is a commentary on the following: Fischer U, Koga M, Strbian D, Branca M, Abend S, Trelle S, Paciaroni M, Thomalla G, Michel P, Nedeltchev K, Bonati LH. Early versus later anticoagulation for stroke with atrial fibrillation. New England Journal of Medicine. 2023 May 24.

Summary of the findings

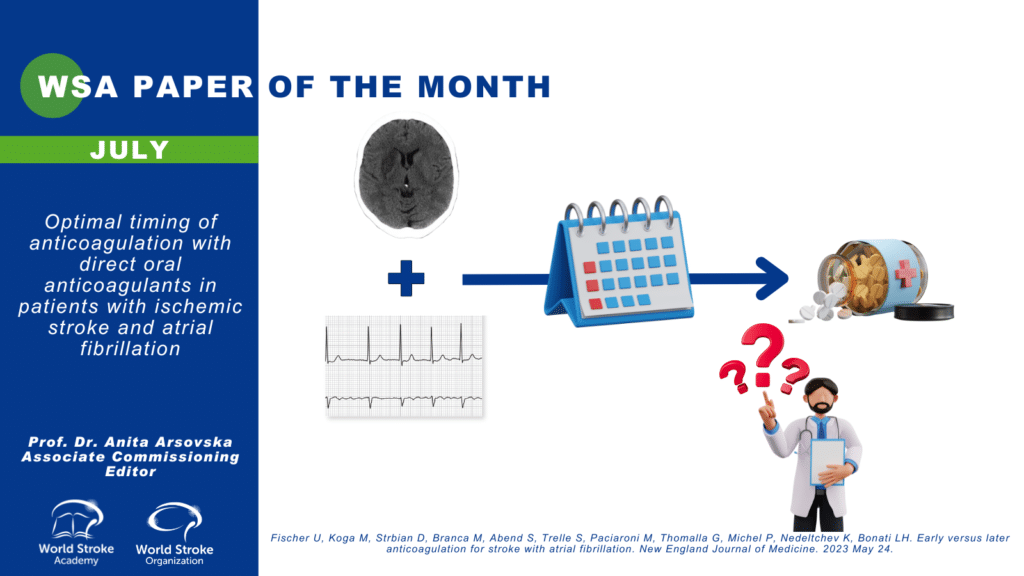

The authors performed an open-label trial at 103 sites in 15 countries to analyze the effect of early vs later initiation of direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) in persons with atrial fibrillation (AF) who have had an acute ischemic stroke (1). They included 2013 participants (37% with minor stroke, 40% with moderate stroke, and 23% with major stroke). Of them, 1006 were assigned to early anticoagulation (within 48 hours after a minor or moderate stroke or on day 6 or 7 after a major stroke) and 1007 on later anticoagulation (day 3 or 4 after a minor stroke, day 6 or 7 after a moderate stroke, or day 12, 13, or 14 after a major stroke). The primary outcome was a composite of recurrent ischemic stroke, systemic embolism, major extracranial bleeding, symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage, or vascular death within 30 days after randomization. Secondary outcomes included the components of the composite primary outcome at 30 and 90 days. By 30 days, a primary-outcome event occurred in 29 participants (2.9%) in the early-treatment group and 41 participants (4.1%) in the later-treatment group. Recurrent ischemic stroke occurred in 14 participants (1.4%) in the early-treatment group and 25 participants (2.5%) in the later-treatment group by 30 days and in 18 participants (1.9%) and 30 participants (3.1%), respectively, by 90 days. Symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage occurred in 2 participants (0.2%) in both groups by 30 days. Authors concluded that the incidence of recurrent ischemic stroke, systemic embolism, major extracranial bleeding, symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage, or vascular death at 30 days ranged from 2.8 percentage points lower to 0.5 percentage points higher (based on the 95% confidence interval) with early than with later use of DOACs.

Commentary

AF and stroke risk

AF is the most common cardiac arrhythmia and one of the main causes of stroke, heart failure and death worldwide (2). It has been estimated that 25% of adults in Europe and the United States will eventually develop AF during their lifetime (3,4). The incidence of AF has increased because there is a higher percentage of its detection, as well as the aging of the population and the existence of comorbidities that predispose to AF (5,6). Cohort studies showed that approximately 20% to 30% of patients suffering from ischemic stroke have previously been diagnosed with AF, either during or after the initial event (5, 7). AF-associated stroke has a 46% risk of significant disability (modified Rankin scale score of 3–5) and a 13.5% risk of death (8). The risk of stroke is particularly high in patients with AF who have had a previous transient ischemic attack (TIA) or stroke (2).

Use of DOACs after cardioembolic stroke

The use of DOACs after cardioembolic stroke has been analyzed in several observational studies. The SAMURAI-NVAF study showed that no occurrence of intracerebral hemorrhage was observed after initiation of DOAC at a mean period of 4 days after stroke (9). In another observational study, there was no significant difference in the occurrence of recurrent ischemic events after initiation of DOAC, within a period of less than or greater than 7 days from the initial event (10). The occurrence of early relapse and major bleeding in patients with acute ischemic stroke and AF receiving DOACs after the initial event was evaluated in the prospective observational multicenter RAF-DOAC study. An early recurrent event occurred in 32 patients (2.8%) and major bleeding in 27 patients (2.4%). The overall rate of relapse and major bleeding was 12.4% for patients who started receiving DOACs up to 2 days after the acute stroke, 2.1% for those who started between 3-14 days, and 9.1% for those who started after 14 days and more so after the first stroke. The combined rate of relapse and major bleeding was 5% in DOAC-treated patients after acute stroke (11).

Optimal time for introduction of OAC

Up to now, the optimal introduction of OAC depended on the type and severity of stroke. Usually in patients with TIA, anticoagulant therapy was introduced after 1 day, in case of mild stroke (NIHSS score <8), after 3 days, in case of moderate stroke (National Institute of Stroke Scale -NIHSS score 8-16) after 6 days, in severe stroke (NIHSS score > 16) after 12 days (12). In patients with ICH, OAC therapy is started after 4-8 weeks, that is, according to the doctor’s assessment (12).

RTCs initiated to provide optimal timing of anticoagulation in the early phase of ischemic stroke

-TIMING (Timing of Oral Anticoagulant Therapy in Acute Ischemic Stroke With Atrial Fibrillation) was a registry-based, randomized, noninferiority, open-label, blinded end-point study at 34 stroke units using the Swedish Stroke Register for enrollment and follow-up (13). Within 72 hours from stroke onset, 888 patients were randomized to early (≤4 days) or delayed (5–10 days) DOAC initiation. The primary outcome was the composite of recurrent ischemic stroke, symptomatic ICH, or all-cause mortality at 90 days. It occurred in 31 patients (6.89%) assigned to early initiation and in 38 patients (8.68%) assigned to delayed DOAC initiation(absolute risk difference, -1.79% [95% CI, -5.31% to 1.74%]; Pnoninferiority=0.004). Ischemic stroke rates were 3.11% and 4.57% (risk difference, -1.46% [95% CI, -3.98% to 1.07%]) and all-cause mortality rates were 4.67% and 5.71% (risk difference, -1.04% [95% CI, -3.96% to 1.88%]) in the early and delayed groups, respectively. No patient in either group experienced symptomatic ICH. The authors concluded that early initiation was noninferior to delayed start of DOAC after acute ischemic stroke in patients with AF. Numerically lower rates of ischemic stroke and death and the absence of symptomatic ICH implied that the early start of DOAC was safe and should be considered for acute secondary stroke prevention in patients eligible for DOAC treatment.

Ongoing studies

– START (Optimal delay time to initiate anticoagulation after ischemic stroke in atrial fibrillation) is a prospective randomized clinical trial that is aiming to determine if there is an optimal delay time to initiate anticoagulation after AF-related stroke that optimizes the composite outcome of hemorrhagic conversion and recurrent ischemic stroke (14).The study will enroll 1500 total subjects split between a mild to moderate stroke cohort (1000) and a severe stroke cohort (500). The primary outcome event is the composite occurrence of an ischemic or hemorrhagic event within 30 days of the index stroke. Secondary outcomes are also collected at 30 and 90 days.

– OPTIMAS (Optimal timing of anticoagulation after acute ischemic stroke with AF) is a multicenter randomized controlled trial with blinded outcome adjudication (15). Participants with acute ischemic stroke and atrial fibrillation eligible for anticoagulation with a direct oral anticoagulant are randomized 1:1 to early or delayed initiation.The primary outcome is a composite of recurrent stroke (ischemic stroke or symptomatic ICH) and systemic arterial embolism within 90 days. Secondary outcomes include major bleeding, functional status, anticoagulant adherence, quality of life, health and social care resource use, and length of hospital stay. OPTIMAS aims to provide high-quality evidence on the safety and efficacy of early direct oral anticoagulant initiation after atrial fibrillation-associated ischemic stroke.

Clinical significance of the ELAN trial

The ELAN trial found that DOACs can safely be started much earlier than our standard practicein patients with acute ischemic stroke and AF.Earlier DOAC treatment was associated with a lower rate of ischemic events (thats ranged from 2.8 percentage points lower to 0.5 percentage points higher), with similar bleeding risks than delay start (1). The authors point out that there is no reason to delay DOAC treatment in these patients. The results suggest that early DOAC treatment is reasonable; it is unlikely to cause harm and it is probably better at reducing ischemic events.This trial would change clinical practice given that ELAN results reduce the uncertainty surrounding the risks of early use of DOACs. As a result, clinicians are more reassured that starting DOAC treatment early in these patients will increase the risks ofadverse events.

Conclusion

Optimizing the secondary stroke prevention in patients with AF is crucial in order to reduce the overall burden of stroke. The ELAN trial provides supporting evidence to encourage clinicians to start DOACs early in patients with AF after acute ischaemic stroke.

References

- Fischer U, Koga M, Strbian D, Branca M, Abend S, Trelle S, Paciaroni M, Thomalla G, Michel P, Nedeltchev K, Bonati LH. Early versus later anticoagulation for stroke with atrial fibrillation. New England Journal of Medicine. 2023 May 24.

- Rahman F, Kwan GF, Benjamin EJ. Global epidemiology of atrial fibrillation. Nat Rev Cardiol 2014; 11(11):639–54.

- Heeringa J, van der Kuip DA, Hofman A, et al. Prevalence, incidence and lifetime risk of atrial fibrillation: the Rotterdam study. Eur Heart J 2006; 27(8):949–53.

- Lloyd-Jones DM, Wang TJ, Leip EP, et al. Lifetime risk for development of atrial fibrillation: the Framingham heart study. Circulation 2004;110(9): 1042–6.

- Kishore A, Vail A, Majid A, et al. Detection of atrial fibrillation after ischemic stroke or transient ischemic attack: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Stroke 2014;45(2):520–6.

- Schnabel RB, Yin X, Gona P, et al. 50 year trends in atrial fibrillation prevalence, incidence, risk factors, and mortality in the Framingham heart study: a cohort study. Lancet 2015;386(9989):154–62.

- Grond M, Jauss M, Hamann G, et al. Improved detection of silent atrial fibrillation using 72-hour Holter ECG in patients with ischemic stroke: a prospective multicenter cohort study. Stroke 2013; 44(12):3357–64.

- Stroke sentinel national audit. Atrial fibrillation outcome data, 2018-19 annual clinical audit results. Kings college London and the health quality improvement programme. Available at. https:// www.strokeaudit.org/Documents/National/Clinical/ Apr2018Mar2019/Apr2018Mar2019-CCGAF Report .aspx.

- Toyoda K, Arihiro S, Todo K et al. SAMURAI Study Investigators. Trends in oral anticoagulant choice for acute stroke patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation in Japan: the SAMURAI-NVAF study. Int J Stroke 2015;10:836–842.

- Seiffge DJ, Traenka C, Polymeris A et al. Early start of DOAC after ischemic stroke: risk of intracranial hemorrhage and recurrent events. Neurology 2016;87:1856–1862.

- Seiffge DJ, De Marchis GM, Koga M. RAF, RAF-DOAC, CROMIS-2, SAMURAI, NOACISP, Erlangen, and Verona registry collaborators. Ischemic stroke despite oral anticoagulant therapy in patients with atrial fibrillation. Ann Neurol 2020; doi: 10.1002/ana.25700.

- Nielsen PB, Larsen TB, Skjoth F et al. Restarting anticoagulant treatment after intracranial hemorrhage in patients with atrial fibrillation and the impact on recurrent stroke, mortality, and bleeding: a nationwide cohort study. Circulation 2015;132:517–525.

- Oldgren J, Åsberg S, Hijazi Z, Wester P, Bertilsson M, Norrving B, National TIMING Collaborators. Early versus delayed non–vitamin k antagonist oral anticoagulant therapy after acute ischemic stroke in atrial fibrillation (TIMING): a registry-based randomized controlled noninferiority study. Circulation. 2022 Oct 4;146(14):1056-66.

- King BT, Lawrence PD, Milling TJ, Warach SJ. Optimal delay time to initiate anticoagulation after ischemic stroke in atrial fibrillation (START): Methodology of a pragmatic, response-adaptive, prospective randomized clinical trial. Int J Stroke. 2019 Dec;14(9):977-982.

- Best JG, Arram L, Ahmed N, Balogun M, Bennett K, Bordea E, Campos MG, Caverly E, Chau M, Cohen H, Dehbi HM. Optimal timing of anticoagulation after acute ischemic stroke with atrial fibrillation (OPTIMAS): protocol for a randomized controlled trial. International Journal of Stroke. 2022 Jun;17(5):583-9.

Written Interview to Prof. Urs Fischer

1. What did you set out to study?

The focus of my research activity is to answer clinically relevant unanswered questions by randomised controlled clinical trials and to bring scientific knowledge in areas where evidence is lacking. Back in 2014, when we designed the “Early versus Late initiation of direct oral Anticoagulants in post-ischaemic stroke patients with atrial fibrillatioN (ELAN)”[1] trial it was unclear when anticoagulation with direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) should be started in people after an acute ischaemic stroke with atrial fibrillation (AF). The pivotal trials comparing DOACs with vitamin K antagonist excluded people with a recent stroke and therefore it was unknown whether an early treatment start might increase the risk of symptomatic intracranial haemorrhage.

2. Why this topic?

The most frequent dilemma in stroke medicine in which I had to take a decision without any evidence was the question of when to start anticoagulation in people with an acute ischaemic stroke and AF. Early initiation can increase the risk of intracranial haemorrhage, whereas late initiation may increase the risk of early stroke recurrence. Previous studies had compared early anticoagulation with heparin or low-molecular-weight heparin with aspirin in people with a cardioembolic ischaemic stroke. From these studies we knew that early anticoagulation with heparin is associated with a significant increase in intracranial haemorrhages. Therefore, after 2010 when four DOACs were approved for use in people with non-valvular AF, physicians were very scared about starting these DOACs early, given the concern that early initiation might increase the risk of intracranial haemorrhage similarly to heparin. In the absence of evidence, some experts suggested initiation of anticoagulation at 1, 3, 6, or 12 days after a transient ischaemic attack, or minor, moderate, or severe ischaemic stroke, respectively (the “1-3-6-12 day rule”). However, as a clinical scientist I want to base my decisions on evidence and not on the opinions of authority figures. We therefore decided to address this dilemma with a randomised controlled trial.

3. What were the key findings?

The study included 2013 participants with an acute ischaemic stroke and AF recruited from 103 different stroke units in 15 different countries in Europe, the Middle East and Asia (India and Japan) between 2017 and 2022. Based on the size and location of the infarct on imaging (i.e. whether the stroke was minor, moderate or major) participants were randomly assigned to an early treatment start or a later, guideline recommended, treatment start. An early start was defined as being within 48 hours of a minor/moderate stroke or day 6–7 following a major stroke. A late start was defined as day 3–4 following a minor stroke, day 6–7 following a moderate stroke, or day 12–14 following a major stroke. The primary outcome was a composite of recurrent ischaemic stroke, symptomatic intracranial haemorrhage, extracranial bleeding, systemic embolism, or vascular death within 30 days after randomisation.

At 30 days, the primary outcome occurred in 29 (2.9%) people in the early and 41 (4.1%) in the late treatment group (risk difference −1.2%, 95% confidence interval for risk difference −2.8% to 0.5%). At 90 days the difference in rate of the composite outcome was −1.9% (95% CI −3.8% to −0.02%). Recurrent ischaemic stroke at 30 days occurred in 14 participants (1.4%) in the early-treatment group and 25 participants (2.5%) in the late-treatment group and symptomatic intracranial haemorrhage occurred in two participants (0.2%) in both groups.

Figure from Fischer U, et al. N Engl J Med. 2023 Jun 29;388(26):2411-2421

4. Why is it important? Or how might these results impact clinical practice?

ELAN finally provides randomised estimates for symptomatic intracranial haemorrhage, major extracranial bleeding, recurrent ischaemic stroke and death from vascular cause in people with acute ischaemic stroke related to AF. The results provide qualitative data that can be of use to clinicians, enabling them to base their decision about when to start anticoagulation on evidence rather than expert guidelines. Using our imaging-based approach physicians can be reassured that an early start is not associated with an increased risk of intracranial haemorrhage, which relieves a lot of anxiety for the treating physicians. Furthermore, rates of ischaemic events, i.e. recurrent ischaemic stroke and systemic embolism, were numerically lower following an early treatment start compared to a later one. Therefore, early treatment initiation is reasonable if indicated or if desired for logistical or other reasons, such as early discharge planning.

Our results are in line with those of the Swedish “Timing of Oral Anticoagulant Therapy in Acute Ischaemic Stroke with Atrial Fibrillation (TIMING)”[2] trial: this trial had to be stopped prematurely after randomisation of 888 participants due to slow recruitment; however, it showed the non-inferiority of an early compared to a late treatment start. There were no symptomatic intracerebral haemorrhages in either of the treatment arms and rates of recurrent ischaemic events were numerically lower following an early (i.e. within 4 days) compared to a later treatment start.

Based on the findings of the TIMING and ELAN trials, early initiation of treatment with DOACs in people with AF-related ischaemic stroke is unlikely to increase the risk of symptomatic intracerebral haemorrhage and is likely to lower rates of ischaemic events.

5. How does ELAN differ from other stroke trials?

The ELAN trial did not follow a classical statistical design and we were pleased that we could convince the scientific experts with our approach, answering the clinical question. ELAN was designed to estimate the treatment effect and the degree of precision by calculating the odds ratio of the predefined outcomes and the corresponding 95% confidence interval. Therefore, we did not test a specific statistical hypothesis for superiority or non-inferiority and hence no p values are shown in the publication. When we designed the trial, there was a lack of high-quality unbiased data on event rates, making it difficult to identify an appropriate non-inferiority margin. Furthermore, the low event rates would have required a very large trial to assess superiority. For illustration, a superiority trial with an event rate of 4.1% in the control population at 30 days and an assumed reduction of 1% would have required a sample size of more than 11,000 people, assuming a 2% loss to follow-up. Such large numbers are neither feasible nor affordable for investigator-initiated academic trials and would not necessarily provide greater clarity concerning patient management. Novel and less expensive trial designs with estimates rather than classical hypothesis-testing may help to answer clinically relevant questions, which would otherwise not be answered.

6. What’s next for this research?

Given the ultra-early treatment start in the ELAN trial, certain subgroups of people were excluded, especially people with a parenchymal haemorrhage type 1. Furthermore, the NIHSS score prior to randomisation in the ELAN trial was rather low, even though one fifth of participants had a severe stroke, one fifth received thrombectomy and one third intravenous thrombolysis prior to randomisation. Last but not least, ELAN used an imaging-based approach, and therefore it is not known whether an early treatment start 4 days after symptom onset is safe and beneficial if selection is not based on imaging. In the United Kingdom, the large “OPtimal TIMing of Anticoagulation After Acute Ischaemic Stroke: a Randomised Controlled Trial (OPTIMAS)”[3] is ongoing and will provide further evidence to help answering this important clinical question. We strongly recommend sites participating in the OPTIMAS trial to keep randomising in order to get more information for people with parenchymal haemorrhage and for those who are very severely affected. Furthermore, an Individual Participant Data Meta-Analysis (IPDMA) of all randomised controlled trials (CATALYST) on early versus late anticoagulation in people with acute ischaemic stroke and AF is planned to gather more evidence on important subgroups.

Another challenge is the management of people with AF and acute ischaemic stroke despite therapeutic anticoagulation at the time of symptom onset. Observational data have shown that recurrence rates in these people are significantly higher than in those who did not receive therapeutic anticoagulation at baseline and that pharmacological interventions such as change in anticoagulation classes or addition of antiplatelets had no relevant impact on outcome. Therefore, new treatment approaches need to be tested. We are extremely pleased that the Swiss National Science Foundation has just funded our “Early closure of Left atrial Appendage for Patients with atrial fibrillation and ischaemic StrokE despite anticoagulation therapy (ELAPSE)” trial, comparing percutaneous left atrial appendage occlusion on top of DOAC therapy versus DOAC therapy alone. This trial is an interdisciplinary collaboration co-lead by cardiology (Prof. Lorenz Räber) and neurology (Prof. David Seiffge) showcasing the potential of collaborative efforts aiming to provide best treatment for this vulnerable patient group.

7. Is there anything you’d like to add?

Academic randomised controlled trials cannot be performed without the help of many other enthusiastic people, and ELAN is a great example of an international team effort. I would like to thank all my colleagues, collaborators and friends worldwide, who helped us to answer this clinically relevant question and who were eager to invest their time and energy in this project. And I would also like to thank all the participants and their families for their willingness to participate in ELAN. Thanks to this incredible support physicians now can base their decision about when to start anticoagulation after AF-associated ischaemic stroke on evidence rather than expert recommendations.

[1] Fischer U, et al. On behalf of the ELAN Investigators. Early versus Later Anticoagulation for Stroke with Atrial Fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2023 Jun 29;388(26):2411-2421

[2] Oldgren J, et al. Early Versus Delayed Non-Vitamin K Antagonist Oral Anticoagulant Therapy After Acute Ischemic Stroke in Atrial Fibrillation (TIMING): A Registry-Based Randomized Controlled Noninferiority Study. Circulation 2022;146(14):1056-1066.

[3] Best JG, Arram L, Ahmed N, et al. Optimal timing of anticoagulation after acute ischemic stroke with atrial fibrillation (OPTIMAS): Protocol for a randomized controlled trial. International journal of stroke: official journal of the International Stroke Society 2022; 17(5): 583-9.