The Paper of The Month – November

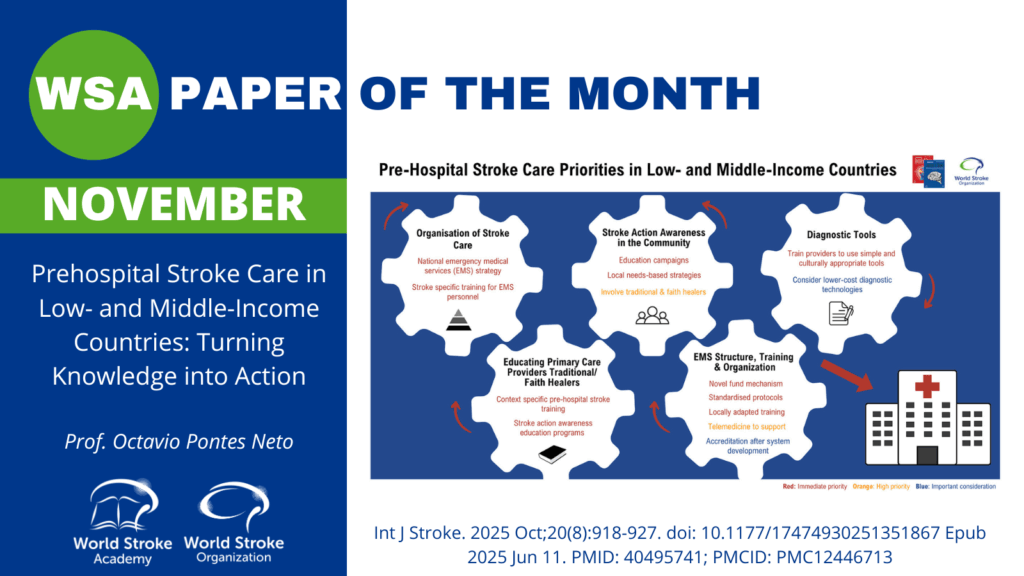

17 Nov 2025Prehospital Stroke Care in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: Turning Knowledge into Action

Prehospital Stroke Care in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: Turning Knowledge into Action

Prof. Octavio Marques Pontes-Neto, MD, PhD – Editor-in-Chief, World Stroke Academy

This article is a commentary on the following: Prehospital stroke care in low- and middle-income countries: A World Stroke Organization (WSO) scientific statement. Int J Stroke. 2025 Oct;20(8):918-927. doi: 10.1177/17474930251351867. Epub 2025 Jun 11. PMID: 40495741; PMCID: PMC12446713.

Commentary:

This month’s featured statement from the World Stroke Organization addresses the one of the most fragile links in the stroke chain of survival across low- and middle-income countries (LMICs): the journey from symptom onset to hospital door. The document reframes prehospital care as a disciplined set of system actions that can be implemented now: public recognition of stroke, rapid activation of transport, structured pre-arrival notification, and early clinical triage. Each action should be adapted to local realities and resource constraints. By organizing recommendations around feasibility and context, it provides a pragmatic roadmap to reduce avoidable delays and prevent disability and death where the burden of stroke is greatest.

The statement opens with a clear situational diagnosis: in many LMICs, community awareness of stroke warning signs remains low, emergency medical services (EMS) are under-resourced or absent, and transport often depends on informal means, compounding onset-to-door times. Against this backdrop, culturally tailored public campaigns (e.g., FAST/Stroke 1-2-0 and school-based programs), delivered through trusted local channels, are presented as high-yield, low-cost interventions. Crucially, the guidance emphasizes that awareness efforts must be coupled with simple, standardized call-to-action messages that direct families to prioritize EMS or designated referral hubs, rather than first visiting non-urgent facilities where time is lost.

Training focuses on those who truly make first contact: primary-care providers, community health workers, lay responders, and, where present, paramedics. The statement encourages rapid adoption of simple bedside tools for recognition and triage (e.g., FAST/CPSS), with NIHSS used when feasible to harmonize communication with hospital teams. Telemedicine is highlighted as a force multiplier that can upgrade decision-making in peripheral settings, support prehospital triage, and extend specialist input to remote regions, while acknowledging the need for robust evaluation of effectiveness and cost-effectiveness in LMIC contexts. Pre-arrival notification, by radio, phone, or low-bandwidth apps, is promoted as a critical bridge to shorten door-to-needle and door-to-groin times once patients reach hospital care.

On organization and policy, the statement calls for funded national or regional EMS strategies, protocolized prehospital pathways, and public-private arrangements to scale dispatch centers and ambulances, supplemented where necessary by trained lay networks and tiered referral hubs. The authors are appropriately cautious about emergent technologies such as point-of-care biomarkers (e.g., GFAP for hemorrhage), near-infrared spectroscopy, and AI-enabled stroke detection: promising complements rather than replacements for fundamentals like reliable transport, clear protocols, and continuous training. Certification programs can support quality, but the guidance wisely prioritizes earlier investments that yield faster returns: workforce, standard operating procedures, and real-time process monitoring.

Finally, the statement sets a near-term research and implementation agenda tailored to LMICs: trials of culturally adapted awareness campaigns with hard process endpoints (EMS use, onset-to-door time), low-cost rapid-response models for urban and rural settings, tele-triage/tele-consult solutions linked to referral hubs, and protocols that explicitly include TIA and minor stroke, commonly neglected sources of preventable harm. It also urges ministries and health systems to adopt prehospital policies now, even when supported by indirect evidence, provided they are paired with continuous evaluation and quality improvement. The overarching message is both pragmatic and optimistic: speed saves brain, but only systems save lives. With disciplined implementation of the basics, guided by local data and iterative improvement, LMICs can make measurable gains in prehospital stroke outcomes today.

References:

- Bosch J, Lotlikar R, Melifonwu R, Roushdy T, Sebastian I, Abraham SV, Benjamin L, Li D, Ford G, Heldner M, Langhorne P, Liu R, Malewezi E, Olaleye OA, Pandian J, Urimubenshi G, Waters D, Zhao J, Rudd A. Prehospital stroke care in low- and middle-income countries: A World Stroke Organization (WSO) scientific statement. Int J Stroke. 2025 Oct;20(8):918-927. doi: 10.1177/17474930251351867. Epub 2025 Jun 11. PMID: 40495741; PMCID: PMC12446713.